The Ottoman Greeks of the United States Project (OGUS) is a multifaceted interdisciplinary research project at the University of Florida. OGUS was established in 2015 with the support of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program and is one of the program’s many projects.

Our main goal is to raise the public’s awareness and inspire scholarly research about the experiences of Ottoman Greek immigrants and refugees in the United States. To achieve this goal, the project is interviewing descendants of immigrants in the US from regions of the former Ottoman Empire which constitute contemporary Turkey.

The OGUS project has thus far collected 251 interviews and is planning more for next year. This essay highlights the structure of the OGUS project and provides examples of each of its components.

Who are the Ottoman Greeks?

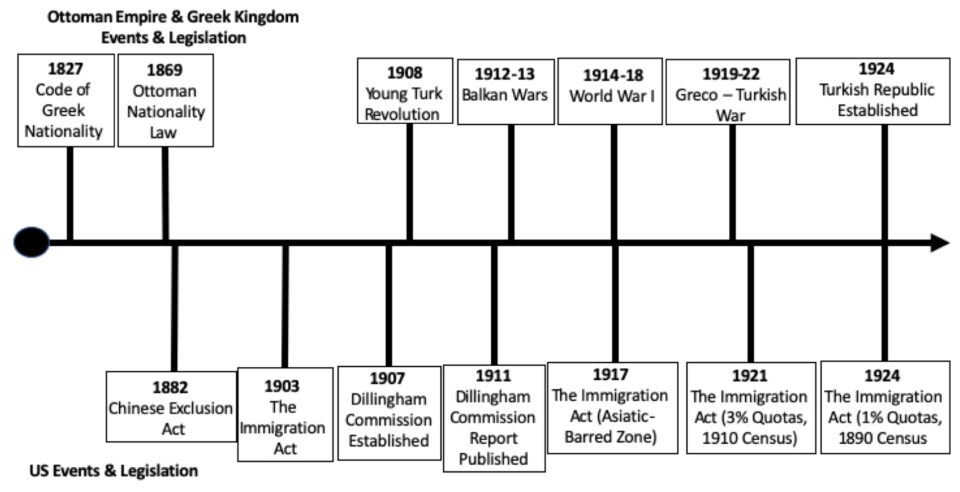

The Ottoman Greek immigrant cohort consisted of Grecophone (Greek-speaking) and Turkophone (Turkish-speaking) Orthodox Christians. The vast majority of Ottoman Greek immigrants and refugees – like other Southeastern European immigrants – arrived in the United States between 1900 and 1923. During this time, major political events motivated their immigration from the Ottoman Empire, while legislation ratified by the US Congress restricted their immigration.

Figure 1 (see image below) provides a timeline of those events and legislation. Some of those events, specifically the Balkan Wars, World War I and the Greco-Turkish War, provided the circumstances under which Ottoman Greeks became the target of ethnic violence that genocide scholars have recognized as genocide [1].

The OGUS project captures oral histories regarding those events. An example of the former was documented during an interview with Shelia, a middle-aged female from Virginia. Shelia’s great-aunt Eugenia and her family made plans in April of 1922 for her wedding in September of that year, the very month that the city of Smyrna (modern Izmir, Turkey) was burned to the ground by Turkish troops.

Sheila recalled the following events surrounding her grandaunt’s wedding.

My great-uncle, his wife, and his children … they were murdered … I think they were marched off somewhere. She used the word machine-gunned to death. And she was supposed to be married actually the weekend after that happened. They had set for the wedding. But when that happened. They killed the groom. They burned the house that he had built … and along with it all of her proika (dowery). And she barely escaped rape, actually. Only because she ran into the area of town where there were European people, and a French family took her in off the streets. The soldiers were after her.”

OGUS also collects information about the journey of Ottoman Greeks to the US including their experiences in labor battalions in the Ottoman Empire, refugee camps in Greece, general experiences in Greece and other countries, stories about the journey itself on transport ships and their arrival to Ellis Island.

Anna, a middle-aged female from Michigan, recollected the following about her mother’s (Irene) and grandmother’s (Antonia) time as refugees on the island of Mytilene (Lesbos, Greece), the same island that contemporary Syrian refugees are located.

We slept on the streets. There we suffered starvation, but we had rations. We were given a pot of chickpeas covered in olive oil two fingers thick. The children would eat with their hands and whatever was left we brought back home. We stayed in Mytilene for two years and then moved to Athens where I was put in an orphanage.

(Photo from Chora, Mytilene, 1927)

Finally, the experiences of Ottoman Greek immigrants in the United States are the central component of the OGUS project. These include stories about identity, gender roles, discrimination, family, community, organizations, the labor market, culinary arts, music and languages.

A salient finding of the project is the racialization of Ottoman Greeks by both Greeks from Greece and by American proponents of Whiteness. The former created a racial boundary around Hellenic identity whose essence was, and continues to be, the Greek state-building narrative. The latter created a racial boundary against anyone who was not of Anglo-Saxon stock. An example of racialization by Greeks from Greece is recounted by “Gus,” a middle-aged male from Ohio.

There’s one story [that] they were Turkophona. [Meaning,] they could only speak Turkish. So, they came here. They go to the [Greek Orthodox] church, but they’re speaking Turkish. And people [were] saying, ‘What are they doing here? Shouldn’t they be in a mosque?’ Well, they understood what they were saying. That offended some people. Then I heard there was a guy called ‘Big Dan. He was a big man. Whenever there was a problem, people always went to ‘Big Dan’. And they said ‘Big Dan’ went to everybody and called them out and said, ‘We’re going on the other side of town and we’re going to start our own congregation.’

In addition to the oral histories, the OGUS project is working closely with the Digital Collections Library at the University of Florida (UFDC) to curate the over 20,000 images of two and three-dimensional artifacts donated by descendants of Ottoman Greek immigrants and refugees. These artifacts are currently being uploaded onto the OGUS Digital Collection. An example from the collection is Figure 2, donated by Evanthia Gatsinaris, a middle-aged female from California whose ancestors were born on the island of Marmara. As refugees, from the former Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Greeks were forced to evacuate their communities with only items they could carry. A significant number of descendants of those refugees retain gold coins that were brought to the US by their ancestors.

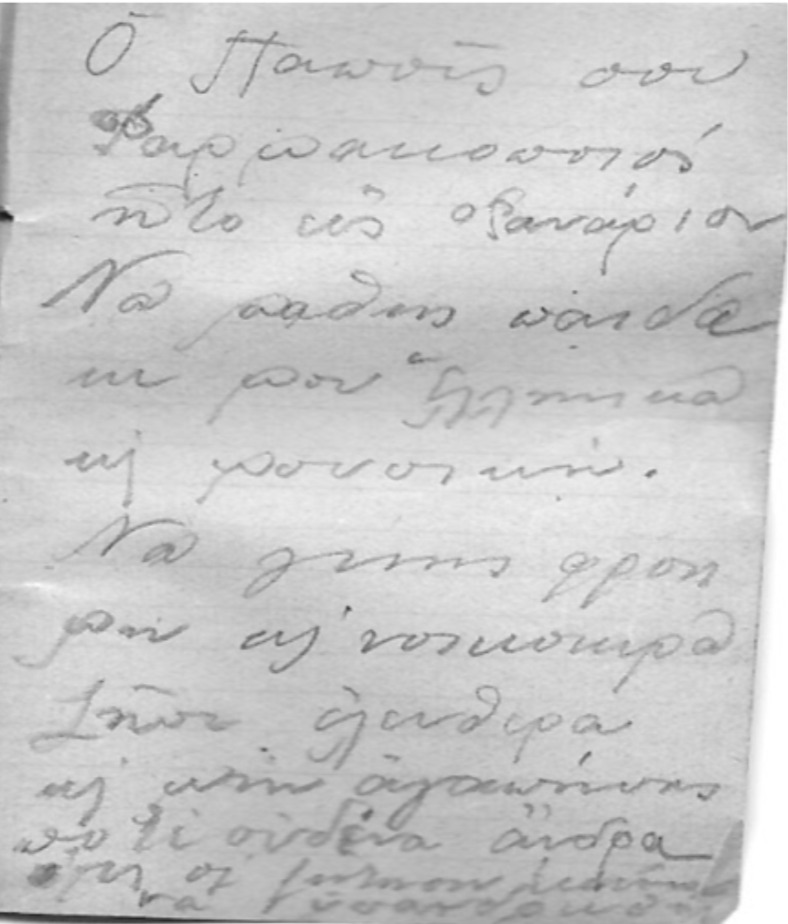

The OGUS UFDC archive also contains images of documents. These documents include immigrants’ autobiographies, correspondence between immigrants and their families in the US, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire. The documents are written in various languages including, English, Greek, Turkish, Ottoman, and local dialects in the Ottoman Empire. Figure 3 is a sample of these documents. It depicts a page from a journal donated by Yvonne Goldman a descendant of immigrants from northeastern Turkey. It is written by Yvonne’s relative, Roxanne Thomades in Greek, and lists words of wisdom to her child.

Three-dimensional images of objects brought from the former Ottoman Empire to the US constitute another category of the archive. An example was donated by Flora Tournidis whose grandparents immigrated from Northeastern Turkey to Canton, Ohio. It is a bronze flask they brought them on their transatlantic journey. Click here to view the three-dimensional model of the flask.

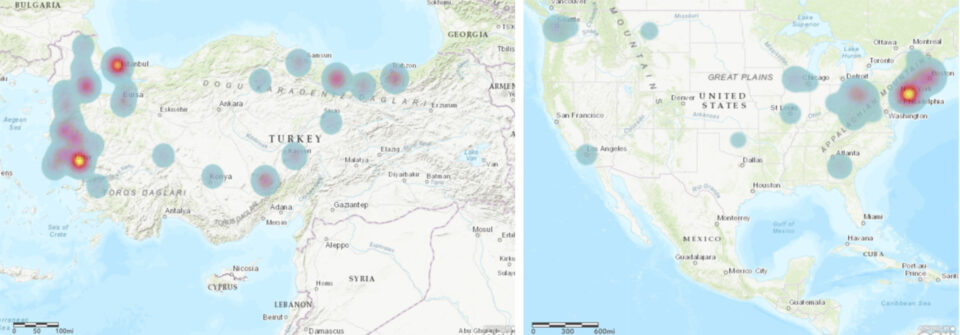

Finally, researchers of the OGUS project are tracing immigration patterns of Ottoman Greek immigrants to the US by collecting data from the Ellis Island Foundation’s online ship manifest archive. This data is being used to construct a GIS map that presents the immigrants’ locations of birth, last residence, ports of departure, ports of call, and final destination. Figure 4 depicts a heat map of the immigrants’ cities of birth in the regions of the Ottoman Empire constituting contemporary Turkey and cities of final destination in the US. Brighter colors on the maps indicate higher populations of immigrants. These maps use a sample of 100 immigrants, however, our researchers have collected over 3000 immigrant entries and the collection process continues.

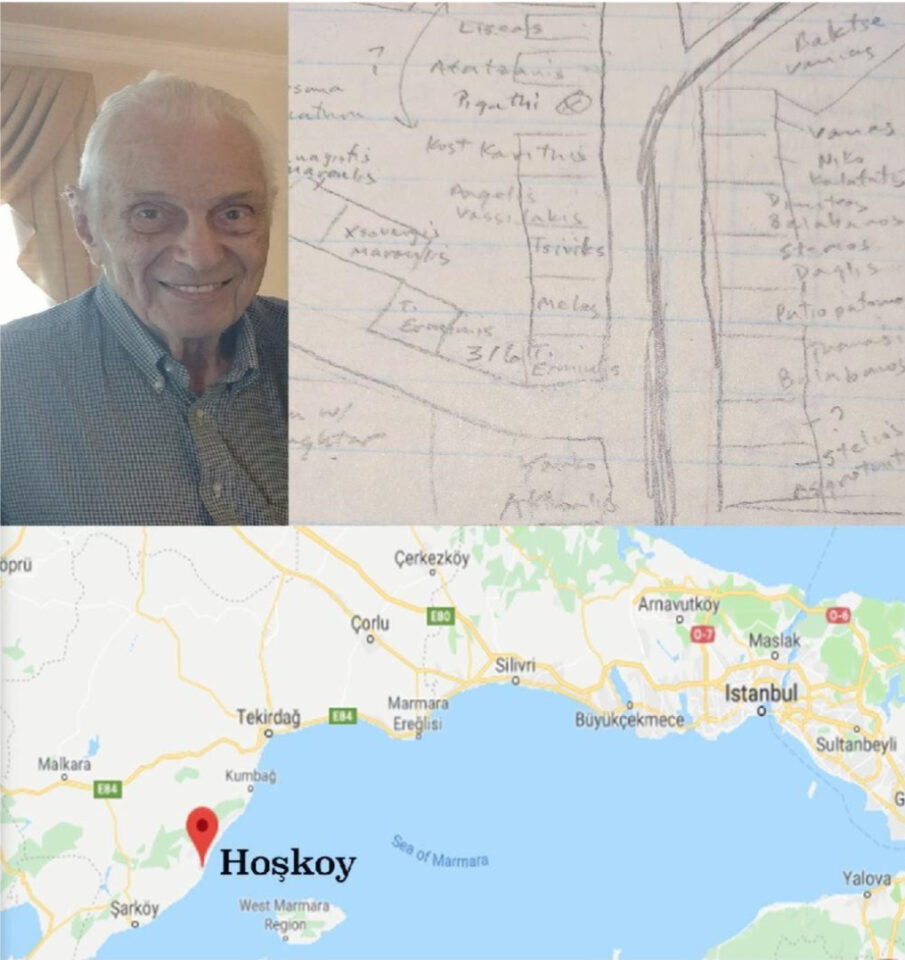

In addition, interview respondents have donated maps constructed from the collective knowledge of their local communities. These maps identify the original locations of family homes in urban and rural communities of the Ottoman Empire and provide the opportunity for researchers to reconstruct three-dimensional models of those communities. Figure 5 depicts one of many in a collection of maps donated by Mr. Diamond Erminy.

Throughout his life Diamond meticulously collected data about the location of the original family homes of immigrants in the towns adjacent to Ganochora. Ganochora and its surrounding towns are located on the European side of Turkey near the coast of the Sea of Marmara. Diamond recently passed away and bequeathed his collection to the OGUS project.

How to get involved in the project

The OGUS project is ongoing. New interviews are being scheduled every six months and images of artifacts are welcomed. If you have any questions, please email us.

Please visit our Facebook page to view our most recent online presentations by clicking here.

If you are interested in learning more about the Ottoman Greeks of the US project, please visit our website.

Finally, to support the OGUS project, visit the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program by clicking here.

Would You Like to Add Your Voice to The Pappas Post?

This post is part of our “Voices” section which aims to broaden the conversations in our community and allow people to share what’s on their mind. These articles in no way reflect the position or opinion of The Pappas Post and our inclusion of a story doesn’t reflect affirmation or denial of the particular point of view. Rather, we seek to give people a platform to share their views.

Interested in submitting your article? Read our guidelines and submit your content today.